As much as a certain shade of blue, fire was aesthetic perfection for the artist Yves Klein. In 1961, a year before his death, he travelled to a French gas company test-centre to make an astonishing series of fire paintings.

As early as 1959, Klein had touched on the role of fire in his imagination, during a lecture at the Sorbonne University in Paris: “Fire for me is the future without forgetting the past. It is the memory of nature. (…) It is gentleness: [Fire] is gentleness and torture. It is cookery and it is apocalypse. It is a pleasure for the good child sitting prudently by the hearth; yet it punishes any disobedience when the child wishes to play too close to its flames. It is well-being and it is respect. It is a tutelary and a terrible divinity, both good and bad. It can contradict itself; thus it is one of the principles of universal explanation. On the other hand, one can, I believe, discuss the quality of fire from the point of view of aesthetic perfection. Fire is beautiful in itself, regardless.“

Throughout Yves Klein’s (1928–62) brief but remarkable career, he would create works that conjured an impression of infinity – be it his famous blue monochromes, his leaps into the void, or his fire paintings, which hauntingly capture the natural phenomenon’s trace on canvas.

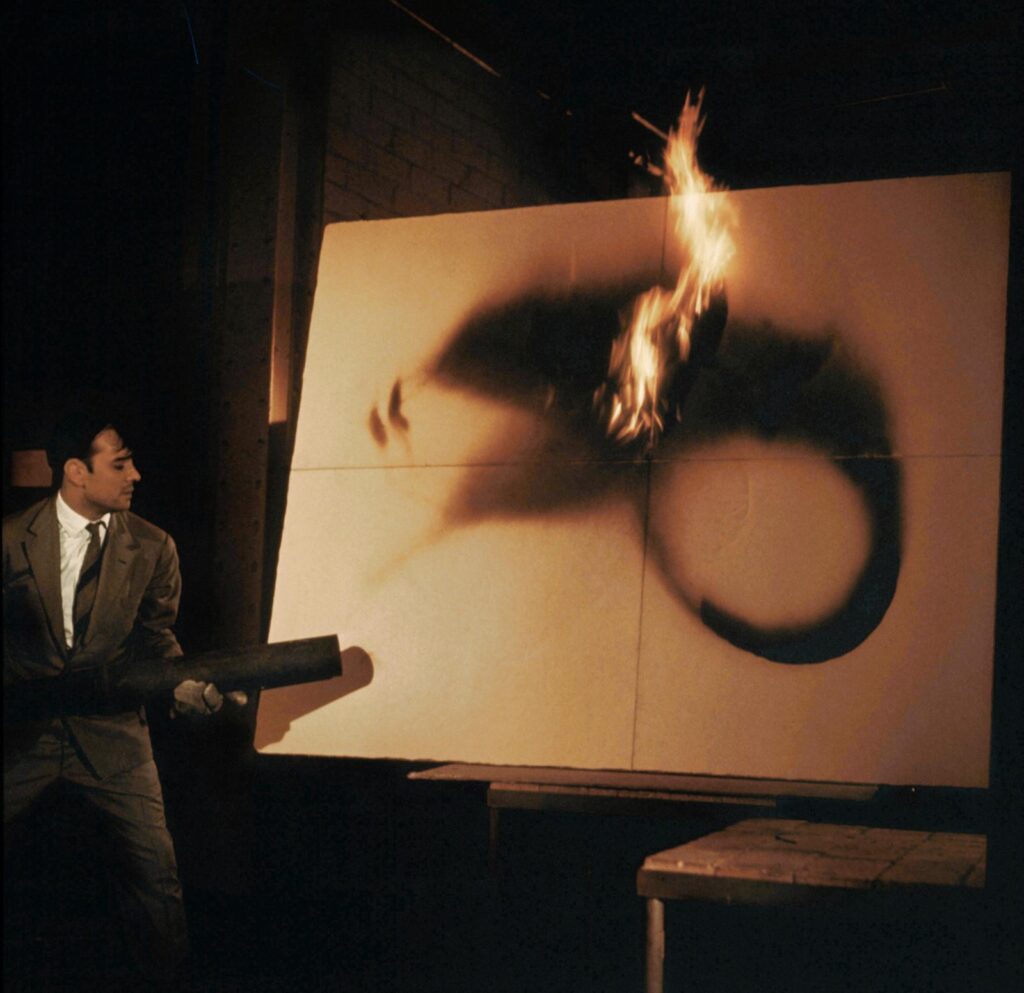

In the spring of 1961, Klein travelled to the Centre d’Essais du Gaz de France, the test centre of France’s national gas company, in Plaine-Saint-Denis. The resulting series of ‘Fire Paintings’ produced that day remain amongst the most elemental and spiritual he ever created.

Klein used an industrial blowtorch weighing forty kilograms, learning how to control the metres-long flame and heat that it emitted. As the artist bowed over each canvas – Swedish cardboard, resistant to combustion – for several minutes at a time, firemen stood at his side, constantly cooling the works with jets of water, and toeing a delicate line as each hovered on the brink of being reduced to ashes.

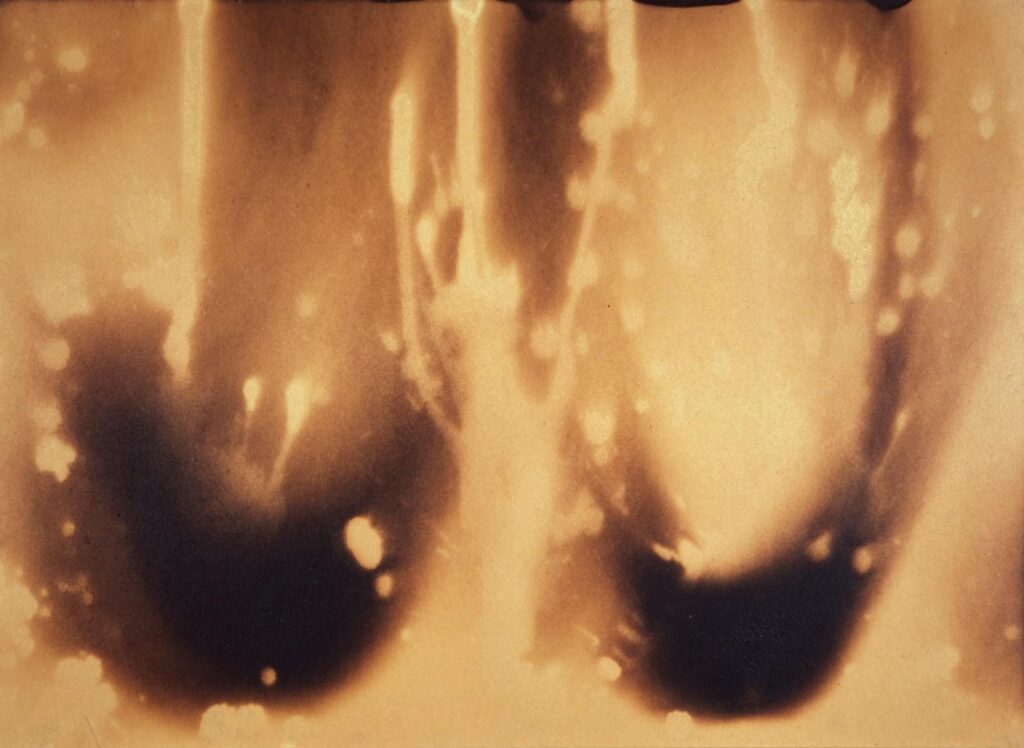

Klein was more alchemist than artist; crackled and streaked by the fire, the wet surfaces morphed from gold to brown and black, unleashing strange apparitions, depending on which approach he used. Almond-shaped geometric forms, ghostly figures on their backs, cottony clouds, or vertical streaks.

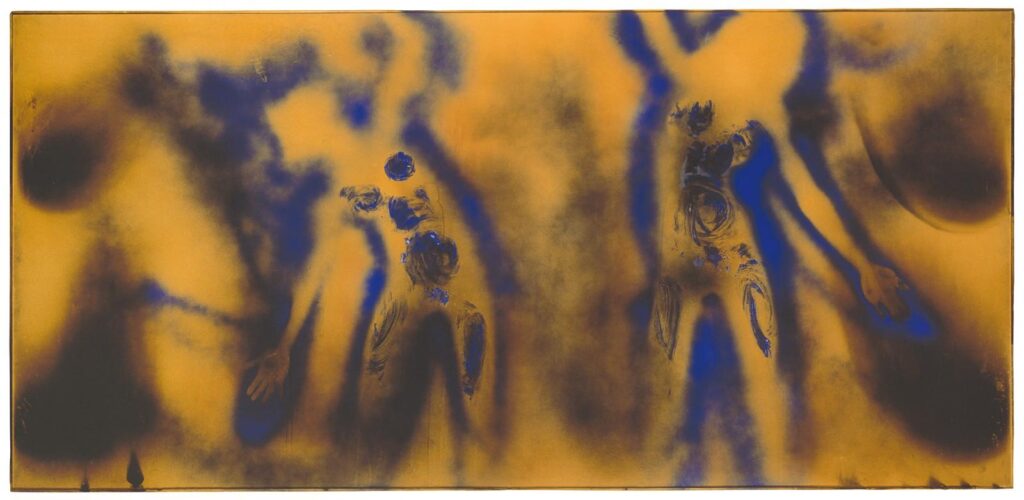

The last painting he made that day, FC1, drew on his so called ‘anthropometries’, by which he imprinted the traces of naked, paint-covered women on his canvases. This time, he sprayed the models with water and asked them to press their bodies to the compressed board, going over those areas with the blowtorch to reveal the spectral trace of their presence as a negative image.

By ‘burning’ their figures onto the paper, he was endowing fire with a similar role to that which light plays in photography – with a nod to the nuclear shadows of the blast victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which had affected him early in his career.

While his experimentation at the test centre ended abruptly when the nude models were discovered – the laboratory’s director was fired – he had used his brief time there to produce some 125 paintings. In 2012, FC1 went on to sell for $36.4 million at Christie’s, setting an auction record for the artist. Check out this video for an in-depth look at the creation of this piece of art.

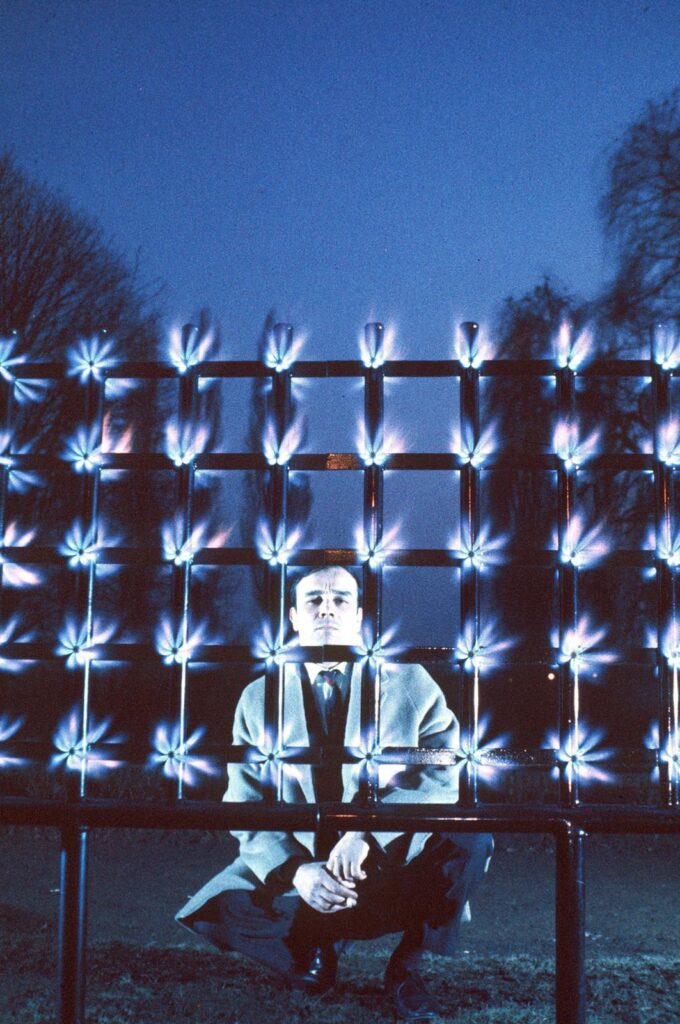

Klein’s exploration of fire was sparked by a 1961 exhibition at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld, Germany, entitled ‘Yves Klein: Monochrome und Feuer’ (Yves Klein: Monochrome and Fire). Featuring an array of techniques it also included his spectacular ‘Fire Wall’ and ‘Fountain of Fire’. The fountain of fire consisted of two columns of flame that shot three metres into the air, while the fire wall comprised fifty Bunsen burners arrayed on their sides in a grid-like pattern, raised a metre or so above the ground, like peculiar stadium lights.

During the exhibition’s opening, Klein arranged for the ‘lights’ to go on as guests gathered on the lawn – a display that ‘suddenly illuminated the twilight’. According to the art critic Pierre Restany, co-founder of New Realism, and author of Yves Klein:The Fire at the Heart of the Void, those who witnessed it were left with ‘Prometheus and Empedocles complexes: attraction, repulsion, bedazzlement and apprehension’, encapsulating fire’s conflicting powers that so fascinated Klien.

‘My works are only the ashes of my art,’ claimed Klein – a trace of a process or happening which is invisible to the eye. For Klein, fire – one of the four elements – was indispensable for getting to grips with absence, with the unseen – the spiritual sense that lies beyond the surface of material things.

Klein was not only influenced by thinkers who had grappled with fire – Gaston Bachelard, or Jung – he was inspired by the palette of fire itself: blue, rose and gold. By combining fire and painting, he captured a moment in time that seemed to speak of the substance of life.

You can learn more about Yves Klein and his works of art here.

Top Image

© Harry Shunk and Janos Kender J.Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. (2014.R.20)

© The Estate of Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris